Overview #

In main-memory databases, when the database size exceeds the main memory size, we need to deploy some buffering strategy that caches the current working set in memory while the rest of the database is stored on disk. There are two approaches we can use:

- Traditional DB buffer pools

- Let the OS handle it via virtual memory

Both approaches impose a high overhead for main-memory databases. Letting the OS handle might be better than traditional DB buffer pools since its overhead only kicks in when the working set exceeds the memory size; with the latter, the overhead is constantly there regardless of the current db size.

In the paper “Anti-Caching: A New Approach to Database Management System Architecture”, DeBrabant, Pavlo et al propose Anti-Caching as a low-overhead alternative for keeping hot data in memory while cold data is evicted/anti-cached to disk. From their paper:

To overcome these problems, we present a new architecture for main memory DBMSs that we call anti-caching. In a DBMS with anti-caching, when memory is exhausted, the DBMS gathers the “coldest” tuples and writes them to disk with minimal translation from their main memory format, thereby freeing up space for more recently accessed tuples… Rather than starting with data on disk and reading hot data into the cache, data starts in memory and cold data is evicted to the anti-cache on disk.

The key features of anti-caching are as follows:

- A database consists of tables (and indices) and each table consists of tuples

- Fine-Grained Eviction: Residency (whether an item is kept in-memory or evicted) is determined at the tuple level rather than at page/block level

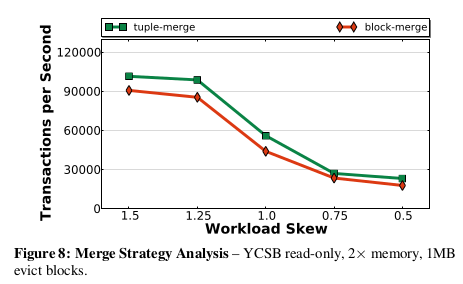

- The tuples are stored in a doubly-linked list.

- As queries are executed, the tuples accessed by a query are moved to the tail.

- Therefore, over a period of time, tuples at the head of the list comprise the least-recently used (LRU) set while those at the tail comprise the most-recently used (MRU) set. This forms an LRU chain.

- As long as all of the database fits the memory size, the only overhead imposed so far is the moving of accessed tuples to the tail. This overhead can be minimized by using a sample of the queries e.g. 1% of queries executed within a given period.

- Once the database reaches a certain memory threshold, the LRU tuples from each tables are gathered into blocks to minimize IO costs and moved to disk (anti-caching). Their block format is similar to their in-memory format - this minimizes the serialization/deserialization cost.

- Throughout the lifetime of a database, a tuple is never copied, it is either in-memory or on-disk. This is contrast with traditional databases whereby the same tuple might be represented at both levels (double-buffering) hence the need to keep both representations consistent. To rephrase it differently, with anti-caching, main memory is the primary storage device/source of truth as to what a tuple’s state is and before a tuple is read or modified it must be added into the LRU chain - the disk only serves as the ‘anti-cache’.

For anti-caching to be applied, the following assumptions must be true:

- Queries’ working sets (tuple’s accessed) must fit in main-memory. The working sets can change though as tuples are added or updated. A different way of stating this is that working sets should be skewed - at any given time only a small fraction of the entire dataset is accessed.

- The metadata used to track evicted tuples should fit in main-memory.

- Lastly, all indexes (primary keys and secondary) must also fit in main-memory.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into the anti-caching approach:

Storage Manager #

During schema creation, a table can either be configured as evictable or non-evictable. Ideally, only small look-up tables that are frequently accessed should be marked as non-evictable. These will reside entirely in main memory throughout the lifetime of the database.

If a table is marked as evictable, the following data-structures are set up for it:

- LRU Chain: an in-memory doubly-linked list of hot tuples

- whenever tuples are accessed (reads or updates), they’re moved to the tail

- evictions start at the head

- Block table: a hash table that stores evicted blocks of cold tuples.

- The keys are the block IDs and the values are the blocks.

- Keys are kept in-memory and the values (blocks) are disk resident.

- Each block has the same size e.g 8KB

- All tuples within a block are from the same table

- OS/ file-system caching of blocks is disabled.

- Evicted Table: In-memory table that maps evicted tuples to the block they reside in plus respective offsets within the block. Indices either store a pointer to the tuple in the LRU chain or to an entry in the evicted table.

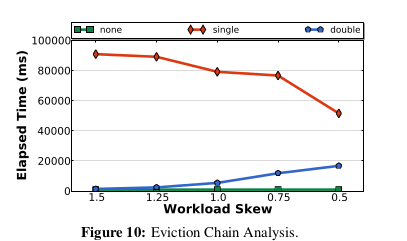

The alternative to a doubly-linked list for the LRU chain is a single-linked list. In both, popping the LRU tuple is O(1). Adding a tuple to the tail is also O(1). However a doubly-linked list allows for both forward and reverse iteration. This allows for queries to start at the tail where the hot tuples reside. This is in contrast with single-linked lists where queries would have to start with the head (LRU entries). Hence the faster execution as demonstrated in the plot below.

Also, as already mentioned, updating the LRU chain imposes some overhead. As such, anti-caching uses what the authors call aLRU; with aLRU, only the accesses from a sample of the queries (1%) are used to update the chain.

Anti-Caching Cold Data (Block Eviction) #

There are two key considerations when determining which data to evict:

- The tables to evict data from

- Amount of data to evict per given table

These are handled as follows: “The amount of data accessed at each table is monitored, and the amount of data evicted from each table is inversely proportional to the amount of data accessed in the table since the last eviction”.

In graphic form:

From there, the cold tuples are popped from the head of the LRU chain and moved into a block buffer. The evicted table is updated and the blocks are written to disk sequentially.

Retrieving data from the anti-cache #

If a query accesses evicted data, the executor places the query in a pre-pass phase then tracks which specific tuples from the block table that the query accesses before rolling back any changes it might have made. From there, the system fetches the required blocks and merges the tuples back into the LRU chain before re-executing the query. This process is summarized in the state diagram blow (retrieved from the paper):

When merging back evicted tuples, there are two strategies:

- Block-Merging: Merge all the tuples in a block back into the LRU chain and

discard the block:

- This is the simplest approach though it also has the highest overhead

- The specific tuples in the block that have been requested are added to the tail (i.e. the ‘hot’ end)

- The rest of the unwanted tuples are added to the head (i.e. the cold end) so that they’ll be the first to be chucked out during the next rounds of eviction.

- Tuple-Merging:

- When retrieving a block, only merge the requested tuples into the LRU chain

- It’s relatively more complicated though is more efficient since we aren’t merging back unwanted tuples that’ll increase the need to carry out more evictions in future

- The block on disk is left as is, i.e. it is not updated. However, we ensure that the evicted table and any data structure that pointed to the merged tuples are updated to reflect the fact that they are back in main-memory.

- The system also keeps track of the number of ‘holes’ per every block. Once the number of holes exceed a certain threshold e.g. 50% of the block, the block is merged with other such blocks.

Possible Further Experiments: Switch LRU for Clock? or Clock-Pro? #

The whole paper is worth a read, especially the experiments and benchmark results section. There are two things I’d love to explore:

One, switch LRU eviction to clock/second-chance eviction. LRU requires using a list and imposes a maintenance overhead (which the authors mitigate by only using a sample of the accesses). Clock on the other hand gives us a bit of freedom with the data structure we can use to hold tuples in memory since we only have to keep a single reference bit per tuple and a separate ring data structure to hold pointers to the tuples. There’s also the clock hand that resets the reference bits or evicts tuples whenever an eviction has to be carried out. It’s worth pointing out that clock is an approximation of LRU so switching to clock shouldn’t change the overall expected behaviour that much.

Two: maybe don’t eagerly merge unevicted tuples. That is, in between the LRU chain and the block table, have a ’lukewarm’ or ’test’ section. From there, tuple’s getting hotter are added into the proper chain and the rest are evicted as blocks. This does add some significant complexity but if we go ahead with using Clock, we might as well upgrade to Clock Pro; In Clock Pro, entries are categorized as either hot or cold. New entries (such as insertions or those unevicted from the block table) are kept in a test period. If they are re-accessed again within that test period, they are upgraded to hot; otherwise, they are kept as cold entries and are amongst the first to be evicted under memory pressure. Relatadely, least recently used hot entries are downgraded to cold but still kept in memory then evicted when necessary.

Regardless, anti-caching is a simple but effective technique for handling larger-than-memory OLTP workloads worth keeping in mind.