Intro #

Today’s paper is Scalable and Robust Latches for Database Systems by Jan Böttcher, Viktor Leis, Jana Giceva, Thomas Neumann and Alfons Kemper. In it, the authors who are also part of the Umbra DB team propose a hybrid lock, a locking implementation that starts off optimistically and only falls back to a pessimistic shared mode locking when needed.

Since a general DBMS should support various kinds of workloads (read-heavy, write-heavy, hybrid), there are certain must-haves and nice-to-haves that locks used should have according to the authors:

- fast and scalable: Locking and unlocking should be fast in cases where there is no contention (no other thread is waiting or currently accessing the item) or very little contention (the critical section is short). Such locks must support both coarse-grained locking e.g. for an entire table and fine-grained locking e.g. for nodes in a b-tree or buckets in a hash table.

- effortless integration with the query engine: In the authors’ case, since they compile queries, the locks used should be able to be compiled quickly into efficient machine code while avoiding external function calls.

- space efficient: Locks should ’not waste unreasonable amount of space’.

For example, the

pthread_mutex_tprovided by some OSs requires 64 bytes “because of binary compatibility with programs that were compiled against ancient implementations that had to be 64 bytes)” [2]. In my system,pthread_mutex_ttakes up 40 bytes. Space-efficient locks (1 byte, 4 bytes) tie into the first point since they allow for fine-grained locking. - graceful contention handling: If two or more threads want to modify the same item concurrently, all but one will have to wait for their turn. The approach used in such contention handling should have minimal to no overhead in cases where there is little contention (such as read-only settings). Threads waiting for their turn should do so quietly i.e. without expending resources. Those threads that want to opt out e.g. user-initiated query cancellation should be able to do so.

Different Locks for Different Folks: OS Mutexes and Spinlocks #

One way of ticking all the above boxes would be to use different locks in different scenarios. This is what pre-2015 Webkit did where they picked either a spinlock or an OS mutex based on the situation [2].

Spinlocks are easy to implement and integrate into a query engine; they can be optimized for low space overhead and have fast lock/unlock under no contention. However, even with some contention, spinlocks end up being quite inefficient:

The simplest spinlocks will make contending threads appear to be very busy and so the OS will make sure to schedule them. This will waste tons of power and starve other threads that may really be able to do useful work. A simple solution would be to make the spinlock sleep – maybe for a millisecond – in between CAS attempts. This turns out to hurt performance on real code because it postpones progress when the lock becomes available during the sleep interval. Also, sleeping doesn’t completely solve the problem of inefficiency when spinning - Locking in WebKit, Filip Pizlo

On the other hand, OS mutexes handle contention quite efficiently since they are able to suspend threads that are waiting allowing for those doing ‘actual’ work to be scheduled in. Unfortunately, they have high space overhead and are rather slow under little to no contention.

Therefore, rather than use one kind of lock exclusively throughout the codebase, the WebKit team picked either kind based on the situation:

WebKit had a mix of spinlocks and OS mutexes, and we would try to pick which one to use based on guesses about whether they would benefit more from uncontended speed or efficiency under contention. If we needed both of those qualities, we would have no choice but to punt on one of them. - Locking in WebKit, Filip Pizlo

In the case of WebKit, they created what they term Adaptive Locks. To give a brief summary, WebKit Adaptive Locks handle contention by spinning a little, 40 times to be precise (the iteration count is derived experimentally though it could safely range between 10 to 60). If the thread still is not able to acquire the lock, it’s placed into a ‘Parking Lot’ - a space-efficient FIFO queue whereby parked threads are able to conserve CPU time and power. The adaptive lock implementation takes 1 byte and the Parking Lot is implemented as a separate data structure outside of the lock which is shared across all threads and locks.

It’s worth noting Webkit is a browser engine, not a database. In most cases though, both teams seem to have the same must-haves and nice-to-haves as far as locking goes. Similarly, both teams settled on a hybrid strategy. In the case of the Umbra DB team, they opted for optimistic locking rather than bounded spinlocks for the ‘fast-path’ and usage of a parking lot to handle contention. Let’s see how their hybrid approach works:

Hybrid Locking Implementation #

As already mentioned, hybrid locking builds upon optimistic locking. If you’re in the database world, you’ve probably already heard of optimistic locking (or rather OCC: Optimistic Concurrency Control as it’s often referred to). Outside of the DBMS world, maybe not. Here’s how optimistic locking works:

- Each data item has a version field

- Whenever a writer modifies the item, it atomically increments the version field

- Readers record the current version of the item at the start.

- After completion, the reader compares the current version with what it observed initially. If both are equal, its read is validated

- Otherwise, the reader has to restart the operation. As such, reads should not cause any side-effects [1].

Optimistic Locking is ideal in situations where there is little to no contention. Readers don’t have to acquire any lock. However, multiple concurrent writers will result in constant restarts and even complete reader starvation. Even with one exclusive writer, concurrent readers have to restart. Furthermore, the system has to keep around older versions of data items until it’s sure there aren’t any readers still accessing them [1].

Since the cost of repeated restarts is non-negligible, the Umbra DB team opt for hybrid approach whereby readers start off optimistically and only fall back to acquiring a shared lock if the version check step fails; writers have to acquire the lock exclusively (i.e. block out other concurrent writers).

A bit of a detour just to introduce the terms shared and exclusive as

pertains locking for non-database folks. A lock can either be acquired in shared

mode or exclusive mode. Shared mode allows for reads only while exclusive mode

allows for both reads and writes. Two or more threads/workers/transactions can

acquire shared locks concurrently i.e. shared locks are compatible. However,

exclusive mode locking allows for only one thread/worker/tx at a time. Since,

we’re dealing with a low-level lock (or rather latch) implementation, one way to

realize shared/exclusive mode locking is via RW (Readers-writer) locks such as

pthread_rwlock_t. Also for DB folk, do excuse me for mixing up locks with

latches - I’ve done so to keep the details here as simple as possible.

Hybrid Locking is designed to be amenable to different implementations of RW locks. In my case I’ll implement it in Rust and use the parking_lot RW lock implementation since it is “smaller, faster and more flexible” than its Rust standard library equivalent. Here’s the code:

use parking_lot::lock_api::RawRwLock;

use std::sync::atomic::{AtomicU64, Ordering};

struct HybridLock {

rw_lock: parking_lot::RawRwLock,

version: AtomicU64,

}

impl HybridLock {

pub fn new() -> HybridLock {

Self {

rw_lock: RawRwLock::INIT,

version: AtomicU64::new(0),

}

}

pub fn lock_shared(&self) {

self.rw_lock.lock_shared();

}

pub fn unlock_shared(&self) {

// SAFETY: this method should only be invoked by caller if lock was

// acquired in shared mode

unsafe { self.rw_lock.unlock_shared() };

}

pub fn lock_exclusive(&self) {

self.rw_lock.lock_exclusive();

}

pub fn unlock_exclusive(&self) {

// TODO overflow checking?

let _ = self.version.fetch_add(1, Ordering::SeqCst);

// SAFETY: this method should only be called if lock was acquired in

// exclusive mode

unsafe { self.rw_lock.unlock_exclusive() };

}

fn try_read_optimistically(&self, read_callback: &dyn Fn()) -> bool {

if self.rw_lock.is_locked_exclusive() {

return false;

}

let pre_version = self.version.load(Ordering::Acquire);

// execute read callback

read_callback();

// was locked meanwhile?

if self.rw_lock.is_locked_exclusive() {

return false;

}

// version is still the same?

let curr_version = self.version.load(Ordering::Acquire);

return pre_version == curr_version;

}

pub fn read_optimistic_if_possible(&self, read_callback: &dyn Fn()) {

if self.try_read_optimistically(read_callback) == false {

self.lock_shared();

read_callback();

self.unlock_shared();

}

}

}

Now the code above is not quite idiomatic Rust since it’s a one-to-one translation of the pseudocode in the paper. More seasoned rust library authors would make it ergonomic and misuse resistant e.g. by providing Mutex Guards, but this should suffice for demonstration. Optimistic readers have to check if the lock is held exclusively both before and after executing the read since to ensure that there isn’t any concurrent modification taking place that would result in inconsistent reads. This is because optimistic readers don’t block writers, it’s only when readers fall back to shared mode that they are able to block writers.

Of note, this implementation ticks all the boxes. It’s fast, scalable, lightweight (16 bytes) and handles contention gracefully. Moreover, reads can only be restarted at most once unlike in a purely optimistic approach where restarts can take place several times.

At a much lower level, successful optimistic reads do not result in any underlying writes for example by updating some state to indicate that reading is taking place. Such underlying writes that modify cache lines lower read performance since the reads end up being bounded by the cache-coherency latencies [1].

Of course, all these is thanks to the parking_lot crate whose authors were in

turn inspired by the WebKit team’s lightweight locks and parking lot approach.

Which brings us to the next point:

Robust Contention Handling #

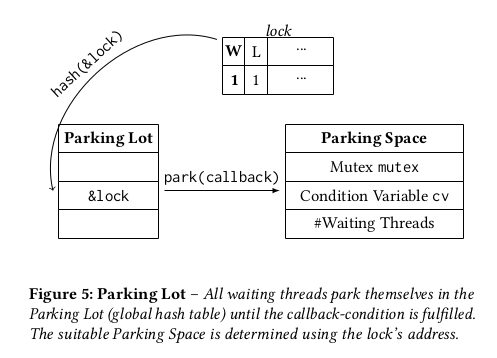

Both Umbra and WebKit use a parking lot to handle contention. This is “a global hash table that maps arbitrary locks to wait queues using their addresses as keys” [1].

When a thread X is about to acquire a given lock and finds that it’s already held by another thread Y, X updates the lock’s wait bit, takes the hash of the lock’s address and uses it to find a spot in the parking lot where it enqueues itself and waits.

Once the thread Y that held the lock is about to unlock it, it first checks if the wait bit is set. In most cases where there’s no contention, the wait bit is unset and all the thread has to do is unset the lock bit and move on (low-overhead unlocking).

However, there was a contending thread X that set the wait bit. Therefore Y has to go the parking lot and find X via the lock’s address plus X’s ID then unpark it (dequeue + resumption) [2].

Parking lot supports multiple threads waiting on the same lock. The size of the parking lot is constant since it only has to support a bounded number of concurrent threads, such as 10 or 500. The WebKit post has more details plus its code is quite readable [2]. The Umbra version does add some additional features such as allowing users to “integrate additional logic like checking for query cancellation, or in the buffer manager to ensure that the page we are currently waiting for has not been evicted in the meantime” [1].

Parting Note #

The respective evaluations carried out by the Umbra and WebKit team are worth checking out. Spoiler alert - hybrid locking + parking lot performs quite well compared to other approaches under various kinds of workloads. The key take-away is that rather than use different locks for different cases throughout the codebase, opting for a hybrid lock implementation allows us to use one kind of lock that ticks all the boxes all while being quite fast and scalable.