Overview #

Leanstore is what you get when you break down the core functionalities of a buffer pool and for each functionality, take the lowest-overheard/highest performance approach possible while keeping modern hardware in mind.

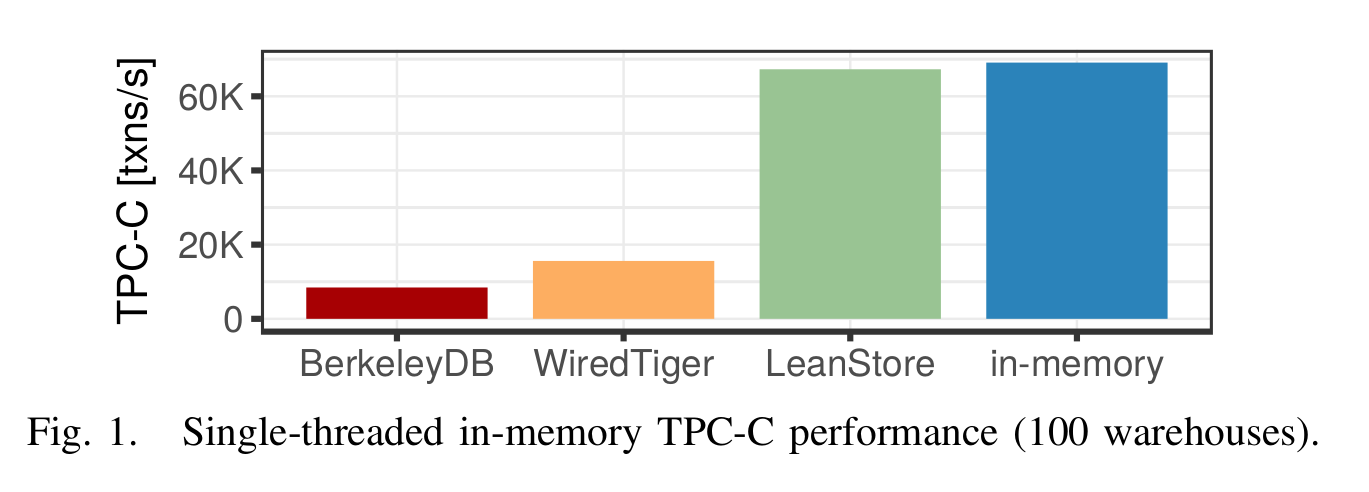

Let’s start of with the numbers and charts showcasing Leanstore’s performance:

Leanstore has two boxes to tick: (1) does it offer great performance in the case where the working set fits entirely in-memory, and (2) does it offer decent larger-than-memory performance as the working set’s size increases.

In the first case where the working dataset fits entirely in-memory, a b-tree implemented on top of Leanstore has almost the same performance as an in-memory b-tree; both of course outperform traditional disk-based b-trees (graph sourced from [1]):

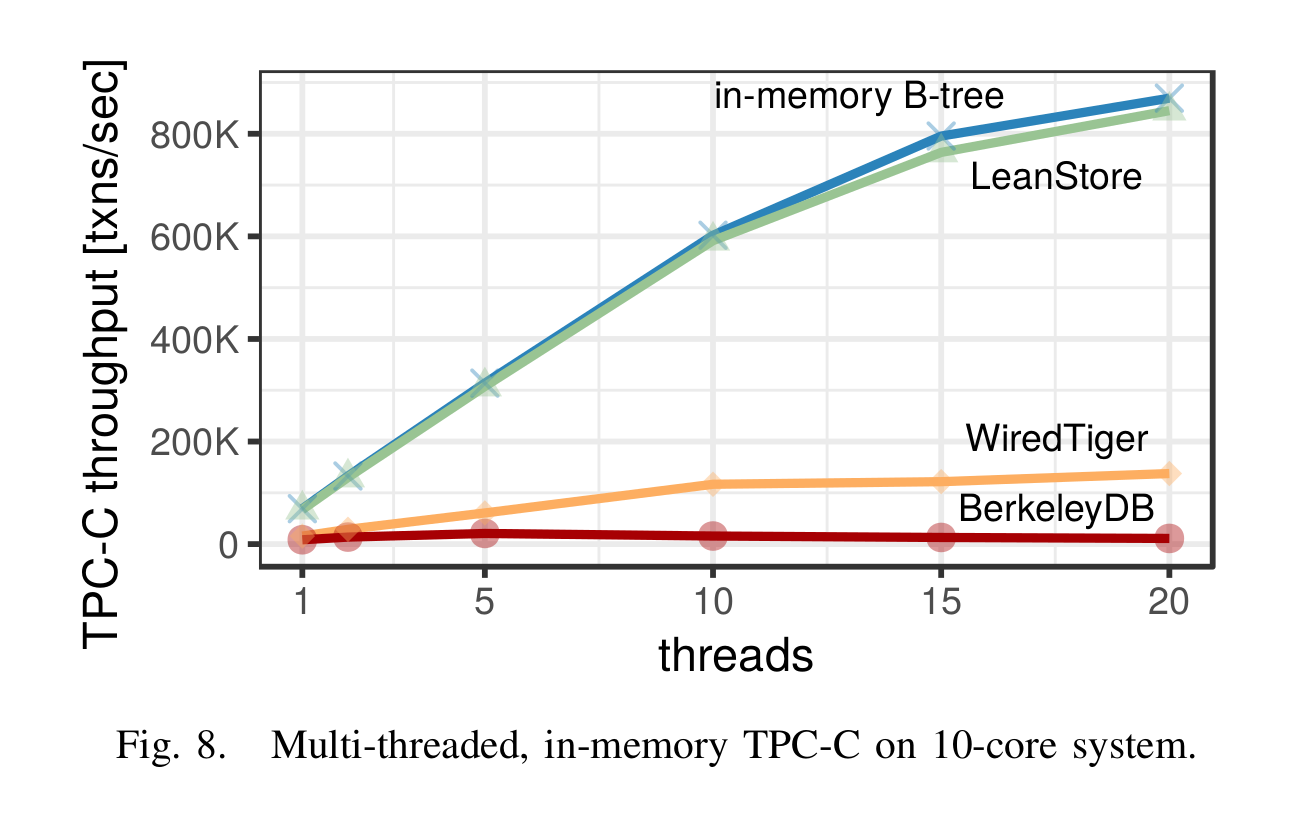

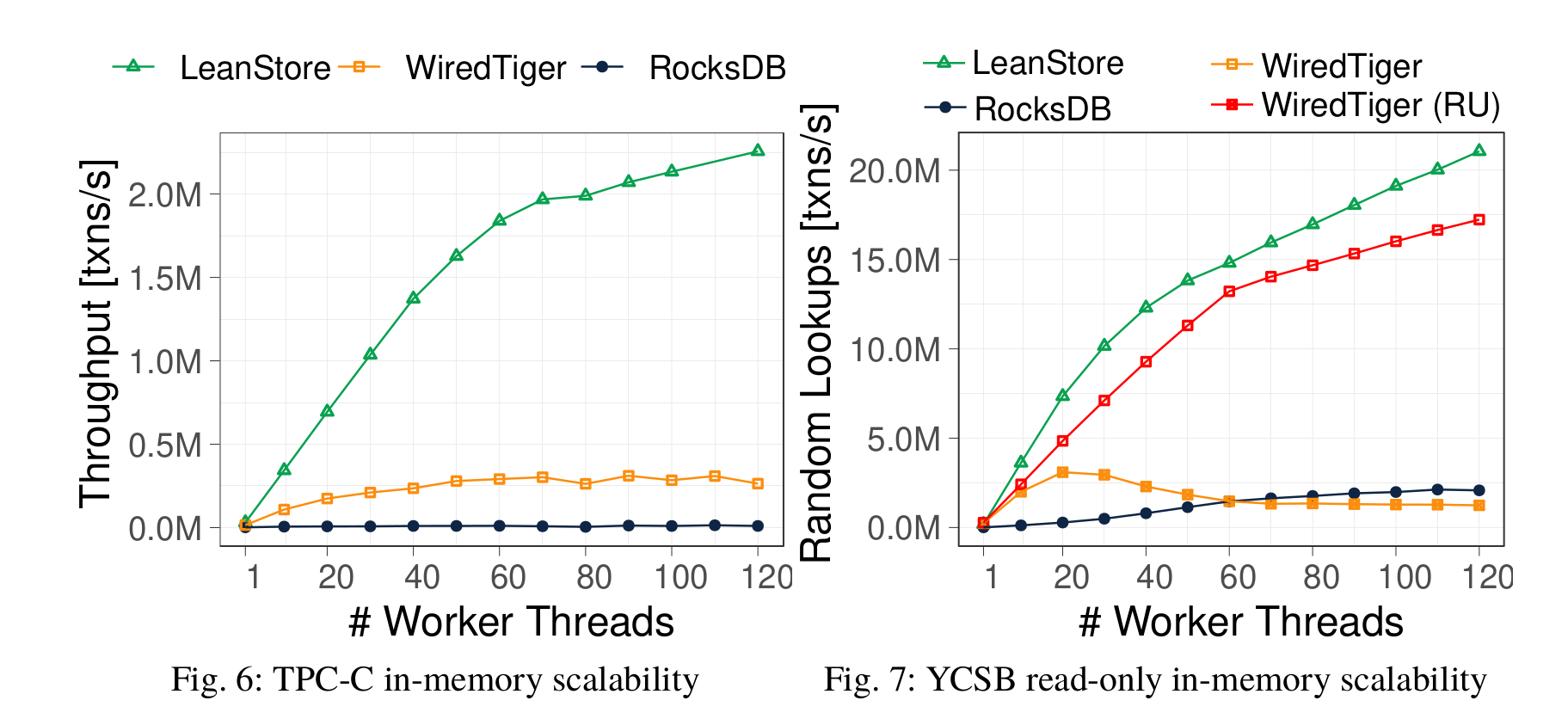

And with multiple threads (graph sourced from [1]):

Leanstore is designed with scalability in mind hence why it scales quite well as number of threads increases. If a page already is in-memory, a thread doesn’t have to acquire any lock such as for the hash table to translate the page ID or for the updating the cache eviction state.

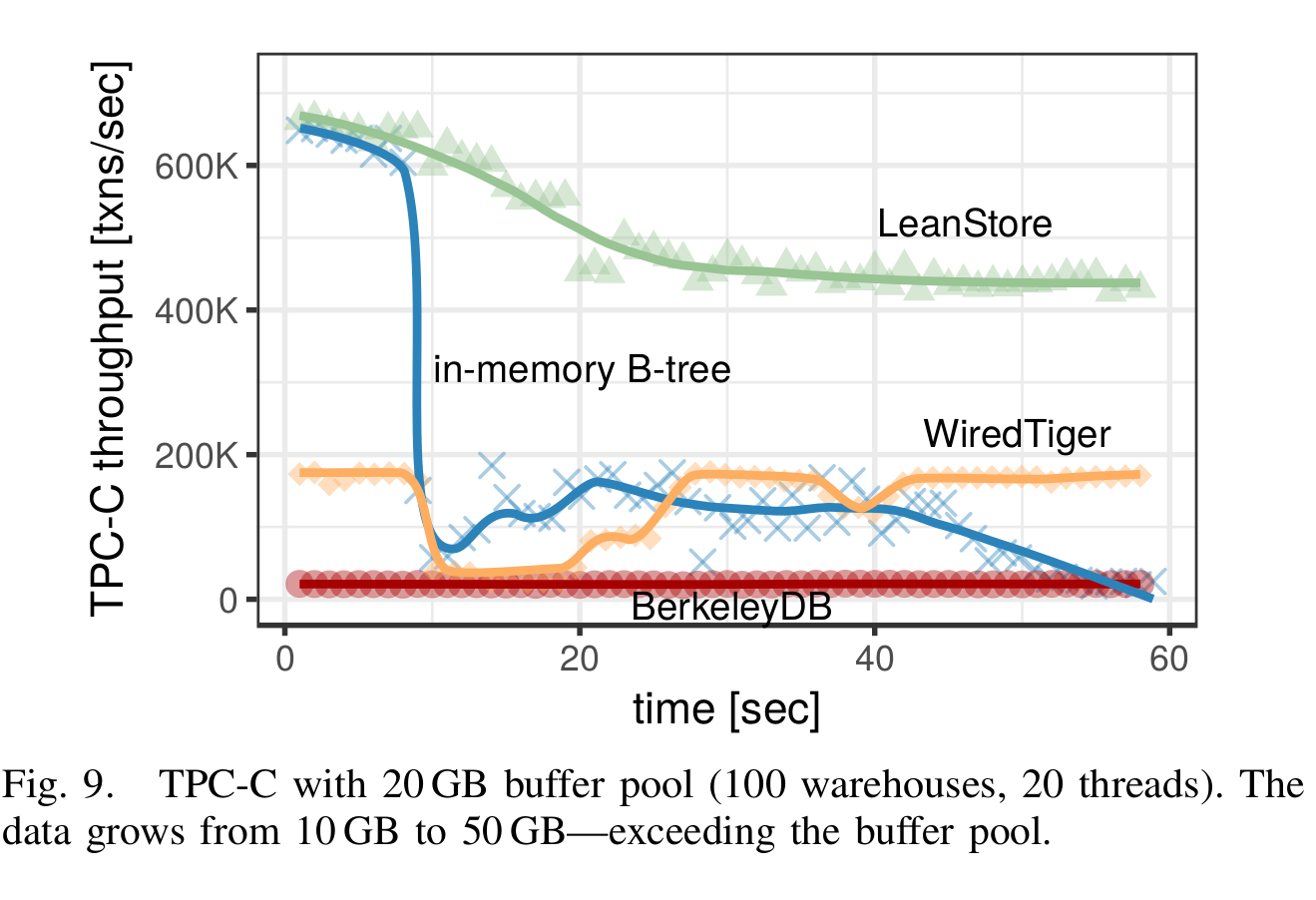

For the second case (larger-than-memory performance), once the working dataset exceeds main-memory, Leanstore offers a smooth off-ramp compared to other systems and even the OS itself (swapping):

As for the core functionalities required out of any buffer pool in a database, the authors list the following:

- Page translation from disk-resident page identifier to in-memory location

- Cache management: determining what pages should be kept in memory and which ones should be evicted once more memory is required

- I/O operations management: loading pages from disk, flushing dirty pages as needed

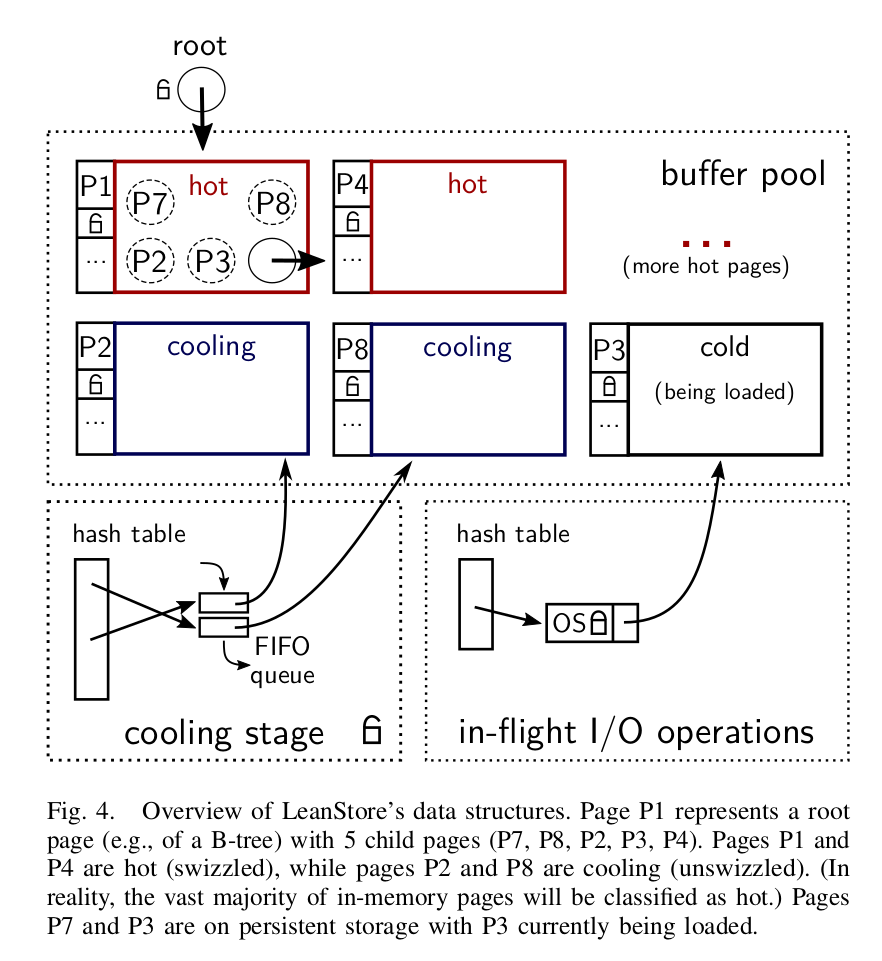

These are handled within 3 separate data structures in Leanstore:

- Buffer pool - handles page translation

- Cooling stage - keeps a pool of pages ready for eviction should space be needed

- I/O Component: manages in-flight I/O operations

Worth mentioning, since multiple threads will be accessing pages, the buffer pool also needs to provide some means for synchronizing threads.

Let’s go over all the functionalities plus their associated data structures:

Page Translation (Pointer Swizzling & I/O Management) #

Traditional buffer pools use a hash map to translate page IDs to buffer frames which in turn hold the in-memory address of the page (if it’s already cached). This adds significant overhead for page hits and is a scalability bottleneck since threads have to acquire a lock before accessing the table.

Leanstore instead opts for pointer swizzling. I’ve covered pointer swizzling before as pertains to buffer pools (the Goetz Graefe et al approach); Leanstore’s approach is almost the same except that it uses virtual addresses directly for pages that are already residing in memory.

A page can only have one other page holding a reference to it - or rather, every page has one parent/one owner (a parent can of course have multiple children such as btree root and inner nodes, or the array of containers in roaring bitmaps). This restriction limits the kind of data structures that can be implemented atop Leanstore. Nonetheless, it is key for simplifying correctness and for high performance (as we shall see in Leanstore’s replacement strategies). To see why a child should only have one parent, suppose Leanstore allowed for a child to have several parents; if a worker thread wants to swizzle the child, it has to ‘consult’ and coordinate with all the other parents so that they are all aware that the child is swizzled. Same case with unswizzling. Such a scenario negates all the performance gains from swizzling, one might as well go back to using a hash map and a traditional buffer pool to centralize all such state.

Back to the actual Leanstore implementation: let’s start with the case where a parent holds a reference to a child page and that page is on secondary storage (has to be fetched/loaded). Here are the steps that a worker thread takes:

- Check that the reference indicates the page is on disk. References take up 8 bytes. One bit is used to indicate whether a page is on disk or in memory. Once in-memory, only 48-bits (6 bytes) out of the 8 byte virtual address in x86 64 bit machine are used for addressing, so we’ve got a bit more leg room to tag metadata compared to the on-disk page ID.

- If the page is on disk, access the I/O component and initialize the I/O as

follows:

- Acquire the (global) lock of the hash table within I/O Component. This hash tables maps on-disk page IDs to I/O frames. The authors argue that this lock will not impede scalability & performance since either way, I/O operations are slower than the preceding lock acquisition [1].

- Create an I/O frame and insert it into the hash table. This consists of an operating system mutex and a pointer to the in-memory location where the page will be loaded to. A key advantage of OS mutexes is that they make threads waiting in a low overhead resource-efficient manner (compared to spin loops).

- Acquire the mutex within the I/O frame before proceeding

- Release the hash table’s global lock

- Issue the read system call. Note that the hash table’s lock is released to enable concurrent I/O operations. Once the read is complete, release the I/O frame’s mutex

- Suppose a different thread had already issued the I/O request for the given page: the current thread will find that there’s already an entry for the page ID in the hash table then block on its mutex until the load is done.

- Once the page is loaded, the reference to the page is swizzled (on-disk page identifier replaced with in-memory address) and access proceeds as normal

Suppose a page was already swizzled; the worker thread has only one step before accessing the page: an if statement to check the bit indicator, that’s it!.

Scaling I/O #

The latest iteration of Leanstore gets rid of the single lock over the hash table for managing I/O operations [6]. Turns out the authors’ initial argument (that a single lock over will not become a bottleneck) got invalidated with SSDs getting faster and their I/O bandwidth increasing:

With one SSD, the single I/O stage with the global mutex in the original LeanStore design from 2018 was enough to saturate the SSD bandwidth. With today’s PCIe 4.0, we can attach an array of, e.g., ten NVMe SSDs…, where each drive can deliver up to 7000 MB/s read bandwidth and 3800 MB/s write bandwidth. In such a system, we need high concurrency to issue a large number of parallel I/O requests to fully utilize all SSDs. The global mutex that protects the I/O hash table would quickly become a scalability bottleneck and prevent us from reaching exploiting the maximum bandwidth that modern flash drives can deliver. [6]

Currently, Leanstore uses a partitioned I/O stage with the page ID determining which partition will be used to handle and synchronize the operation [6]. Each partition is protected by a lock and allows concurrent threads requesting the same page to synchronize their requests and also to ‘park’ as they wait along.

Replacement Strategy 1: LeanEvict #

Memory is a finite resources and eventually, a buffer pool must decide what to evict and what to keep around. Hence all the caching algorithms designed for eviction (LRU, LFU, Clock, Clock-Pro and so on).

Almost all common caching algorithms require some caching state to be updated during a page hit. This range from the simple low-overhead approach in Clock/Second Chance where a bit is set, to the higher-overhead approach in LRU that requires the accessed entry to be moved to the head of a linked list. And as we’ve seen in previous larger-than-memory approaches, developers have to come up with different ways for mitigating this overhead, from only using a sample of the accesses (as is the case in anticaching), to moving the analysis entirely offline to a different thread or process and only logging the tuple accesses (as is the case in Project Siberia and the Stoica and Ailamaki approach).

Leanstore takes a somewhat different philosophy [1]:

Our replacement strategy reflects a change of perspective: Instead of tracking frequently accessed pages in order to avoid evicting them, our replacement strategy identifies infrequently-accessed pages. We argue that with the large buffer pool sizes that are common today, this is much more efficient as it avoids any additional work when accessing a hot page

To reiterate, during a page hit, there’s absolutely no cache state to be updated. In fact, the only overhead is checking if the reference is swizzled (single bit).

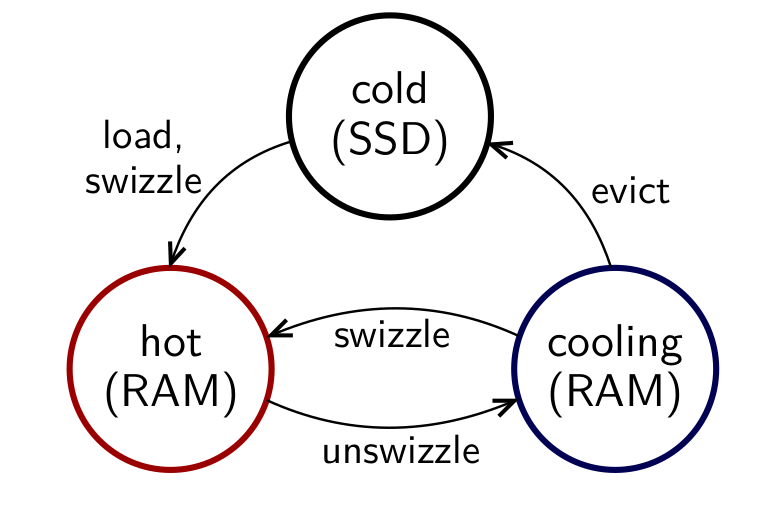

Instead, Leanstore maintains a steady pool of cooling pages that can be evicted should space be needed. These are pages that are speculatively unswizzled (must be referenced through their page IDs) but still kept around in memory. It works this way:

- A random page is picked (as a candidate for eviction) and added to the cooling stage.

- If a page has one or more swizzled children, it’s never unswizzled. Instead, it randomly offers one of its swizzled children for eviction (so much for good parenting). This is key for correctness since swizzled references are only valid for the current program execution and should not be persisted. Furthermore, from a caching perspective, given that only tree-like data structures can be implemented atop Leanstore and worker threads have to traverse from root to target nodes, parent pages will always be at least as hot as their children - or rather, children cannot be hotter than their parents therefore are ‘better’ candidates for eviction.

- Once a page is unswizzled, its parent is ’notified’. Note that a page’s buffer frame also holds a pointer to its parent. Keeping around the parent pointer is not dangerous since children are always unswizzled before their parents.

- Accessing a page that is in the cooling stage causes it to be re-swizzled: the cooling stage can be thought of as a probational stage whereby if the random page picked is in fact hot and should not be evicted, then it is given a period to ‘prove its hotness’ [1].

- The cooling stage consists of a hash map and a FIFO queue. New entrants are added at the head, the oldest cooling page at the tail is evicted should space be needed

- There’s a background thread that iterates through the FIFO queue entries and writes out dirty pages such that upon eviction, a worker thread is not likely to incur the cost of writing a dirty page to disk.

This image (from the paper [1]) shows all the states a page can be in:

At any point in time, a fraction of the cached pages are kept in the cooling stage. The authors recommend a value between 5% - 20% which they arrive at experimentally, with 10% being a decent starting point. If the working set is close to the buffer pool size, a higher percentage means the system will spend a lot of time swizzling and unswizzling hot pages [1].

Also, like any replacement algorithm worth its salt, LeanEvict implements some form of scan resistance: during scans: a worker thread can pre-emptively unswizzle a loaded page and add it to the cooling stage.

For the sake of comparison, the authors collect traces and compare how LeanEvict fares against other cache eviction algorithms. In one particular trace, an optimum caching strategy would give a 96.3% hit rate; LeanEvict has a 92.8% hit rate while LRU is at 93.1%; and 2Q (everyone’s favourite patented caching algorithm) is at 93.8%.

Replacement Strategy 2: Swizzling-Based Second Chance Implementation #

Right when I though Leanstore’s replacement approach couldn’t get any better, the authors go ahead to switch to something simpler that still does the job quite fine - turns out the Cooling Stage was adding unnecessary complexity [6]. Currently, Leanstore uses Second Chance replacement. A swizzled page is assumed to be, or rather starts of as hot, so no need to set the hit bit upon a cache hit as is the case in the textbook version of Second Chance. Hence, accessing a hot page still incurs the same cost as in the initial version.

As for selecting candidates for eviction, a random set of 64 buffer frames is sampled. Within that set, Leanstore carries out the following actions depending on the page’s states:

- Hot page: change page’s status to cool, ‘inform’ the page’s parent that its child is cool. Unlike, the previous implementation whereby the parent swaps the virtual address with a page ID, in the current implementation, the parent only has to tag the virtual address as cool (set the MSB to 1)

- Cool page: if page is dirty write back to disk, or evict immediately otherwise [6]

With this approach in place, Leanstore no longer needs the cooling stage’s hash table and FIFO queue. Also, instead of burdening worker threads with the task of cooling and evicting pages, the current iteration has background Page Provider threads that carry out the cooling and eviction. I’m curious though: if Leanstore still allows for cool pages that are still in-memory to transition back to hot upon a hit and if so, how foreground worker threads that ‘reheat’ a page coordinate with the background page provider threads that might evict that same page. This is probably one of those details that you have to read in the actual code since there’s only so much detail that can be included in the paper.

Synchronization #

With regards to page specific synchronization, Leanstore uses optimistic latches: each page has a counter: writers increment the counter before beginning modifications and readers “can proceed without acquiring any latches, but validate their reads using the version counters instead (similar to optimistic concurrency control)” [1].

What of the case where one thread is reading a page and another thread wants to evict or delete the page (optimistic locks don’t block such threads). To begin with, Leanstore does not allow for unswizzled evicted pages to be reused immediately. Instead it uses epoch-based reclamation to determine when it’s safe to reuse a page. I’m not sure of the degree to which Leanstore’s EBR implementation differs from the textbook/canonical approach, so my following overview of Leanstore’s EBR might be a bit hand-wavey or worse, incorrect (please check the original paper and code for correctness). With EBR, there’s a global epoch that’s incremented every once in a while and each thread also has a local epoch and a flag for indicating that it’s in the critical section. In Leanstore’s case, rather than use a separate flag, the local epoch is set to a sentinel value (infinity). When unswizzling a page (adding it to the cooling stage), the thread doing so also attaches the value of the global epoch at the time of unswizzling. As time goes by, the unswizzled page moves towards the end of the FIFO queue at which point it can be evicted and the resources its holding up (memory pages) be re-used by some other data. However, before eviction, we still are not quite sure if there’s a concurrent reader accessing it. Therefore, we compare the unswizzled page’s epoch with all the local epochs of threads; if it’s strictly less than all the local epochs, then we’re 100% sure that no thread is concurrently accessing the page. Note that if some threads aren’t doing any page accesses currently, then their local epochs are set to infinity which means they won’t impede resource reclamation.

Actually do ignore the last paragraph on Leanstore’s EBR: the current Leanstore implementation does something better than EBR which is nothing at all [2]!. Upon startup, Leanstore pre-allocates the entire memory region for the buffer pool; This memory is not released back to the OS until the process exits [1, 2]. Each buffer frame already contains a version counter that’s used for optimistic locking. When evicting a page, the associated lock is held exclusively and the version counter is incremented; it’s not reset across evictions. If one thread is reading a page and another thread is concurrently evicting it, the latter thread can immediately re-use the page for new data after incrementing the version counter; the reader will compare against the counter’s new value and retry the operation.

The initial implementation for Leanstore relied on spinlocks for exclusive locks. What much can be said about spinlocks - easy to implement, easy to assume they provide high performance but they are a bad idea. Given that many of the researchers developing Leanstore also published papers on hybrid locking and lightweight synchronization primitives, it was only a matter of time before they adopted their techniques within Leanstore [5,6]. In the current Leanstore implementation, pages support optimistic locking (for short reads), shared pessimistic mode (blocks out concurrent writers so no need to restart, for longer page reads) and exclusive mode (mostly for writers, allows for threads waiting in line to be efficiently ‘parked’ rather than loop endlessly) [5, 6].

Unsurprisingly, Leanstore still retains its excellent performance that scales as the number of threads increases [6]. WiredTiger (RU) comes quite close in read-only workloads but that’s only without any concurrency control, shared memory reclamation (hazard pointers) and lock-free techniques whatsoever - the Leanstore numbers are with its synchronization primitives still ’turned’ on (both charts sourced from [6]):

Umbra: Variable-size Pages #

Umbra’s [4] buffer pool builds upon Leanstore by offering variable-size pages. The authors note that [4]:

… a buffer manager with variable-size pages, which allows for storing large objects natively and consecutively if needed. Such a design leads to a more complex buffer manager, but it greatly simplifies the rest of the system. If we can rely upon the fact that a dictionary is stored consecutively in memory, decompression is just as simple and fast as in an in-memory system. In contrast, a system with fixed-size pages either needs to re-assemble (and thus copy) the dictionary in memory, or has to use a complex and expensive lookup logic.

Pages in umbra are partitioned into size classes - the smallest size class is 64

KiB with sizes per class doubling all the way possibly up to the buffer pool’s

entire size. On startup, different private anonymous mappings (not backed by any

files) are reserved for each size class - these don’t consume any physical

memory yet. An unswizzled pointer (page ID) contains both the tag (indicating

it’s disk-resident) and the size class. Upon reading from disk (via the pread)

system class, it’s loaded into the mmap region for its size class and the

pointer is swizzled. Once swizzled, its pointer does not need to contain the

size class it belongs to since that can be derived based on the starting virtual

address. When evicting a page, the madvise system call with the

MADV_DONTNEED flag is used so that the underlying physical pages of

main-memory can be reused.

References #

- LeanStore: In-Memory Data Management Beyond Main Memory - Viktor Leis, Michael Haubenschild, Alfons Kemper, Thomas Neumann

- Lock-Free Buffer Managers Do Not Require Delayed Memory Reclamation - Michael Haubenschild, Viktor Leis

- Leanstore - Viktor Leis - CMU DB Talks

- Umbra: A Disk-Based System with In-Memory Performance - Thomas Neumann, Michael Freitag

- Scalable and Robust Latches for Database Systems - Jan Böttcher, Viktor Leis, Jana Giceva, Thomas Neumann, Alfons Kemper

- The Evolution of LeanStore - Adnan Alhomssi, Michael Haubenschild, Viktor Leis