Intro #

This post is about logging. It contains some advice here and there, and as with most aspects of software engineering, it should be tempered with context. In other words: ‘it depends’ - always factor in the problem at hand rather than adhering blindly to ‘best practices’ that someone wrote on the internet. Now for the best practices which also serves as a quick overview of the rest of the post:

Best Practices #

- Make logs descriptive, but also keep them straight to the point

- Log only actionable information: ‘When a program has nothing to say, it should say nothing’. Logging is a means to an end with the end being being able to run systems confidently, understand these systems behavior and being able to effectively troubleshoot them when things go wrong. Also being able to carry out long-term analyses doesn’t hurt.

- Do consider the audience of the logs. This ties in to the first point. Some logs are meant for humans and should be readily discoverable, others are meant for machines, therefore:

- Use structured logging instead of shoving/concatenating a bunch of attributes into a string. It’s faster to query.

- Use Leveled logging since not every event has the same severity

- Be austere in the number of logging levels used: there’s no point in having a ‘Critical’, ‘Emergency’, ‘Alert’ and ‘Error’ level logs if the application can make do with a single ‘Error’ level.

- Put in place a retention policy: logs don’t have to be kept for eternity: storage costs money and the older the logs the less useful they are for understanding the system’s current behavior

- Logging should be low-overhead. Use performant logging libraries if the default logger is slow/resource intensive.

- Do not log an error then return the error value back to the caller. It might be logged again and again resulting in the same information being repeated several times in the log stream. Errors should be handled only once and logging an error does count as handling it. Therefore, if it’s not the responsibility of a function to handle an error it follows that it’s not its responsibility to log that error. At best what such a function can do is add more context or annotate the error before returning it.

- Audit and transactional logs should be handled separately from operational logs. Do not log audit/transactional details as info-level logs

- Log after an event has happened, not before. In some cases though, this is not feasible, for example, you have to log before your application binds to and listens on a port because after that it enters into an event loop.

- Log in present tense (‘Cannot open file X’) or present continuous tense (‘Listening on port 6000’). The fact that an event occurred is implied by the previous point: ’log after an event’).

- Avoid

log.Fatal. It callsos.Exit(1)after logging the error hencedeferstatements don’t get run. If you must exit the program, preferpanicor bubble up the error back tomain. - In production, use the UTC timezone for timestamps. In development, you can get away with using your local timezone.

- Avoid logging sensitive values that compromise security. If you really have to log them, do anonymize them and also do ensure that downstream log aggregators are secure and compliant.

- Log routing and destination should not be configured within the application -

instead log to

stdoutand in the production environment, the log stream can be redirected as needed (as per the 12 factor Application best practices) - Additionally, log rotation and log compression should not be handled within the application, a separate process/utility should handle it.

- For libraries, if you must log some information, log against an interface then let the caller inject their logger for cases where the logger you’re using internally does not suffice/is not needed

- Favor metrics over logging for low cardinality events that are meant to be aggregated

- Include trace IDs and span IDs for request-scoped logs for correlation with traces.

Formal Introduction #

Logging is outputting a record to indicate the occurrence of an event that’s

occurred in a system. That event can be as simple as ‘hey this program has

started, here’s a “Hello World” message’ or be much more descriptive with 20 or

so attributes. In Go, you’ve got fmt.Println and its cousins. You’ve also got

the log package in the standard library. Plus a whole slew of third-party

logging libraries.

There are various aspects to consider when it comes to logging. Let’s go over some of these aspects:

Leveled Logging #

Log levels indicate the severity of a log entry. They originated as part of Eric Allman’s Sendmail project, particularly syslog. Syslog had the following levels: Emergency, Alert, Critical, Error, Warning, Notice, Informational and Debug, ordered from lowest to highest, most severe to least severe. Some other applications also add a Trace level right after Debug and others use Fatal in place of Emergency. The levels form a hierarchy such that by setting the output’s level to Warning, you’d get all warn-level logs and lower, up to the emergency level, and higher level logs would be filtered out.

The level a log should have tends to be application dependent: what counts as critical for one application might be a warning in a different application. A good practice though is to limit the number of levels used and give each level an unambiguous connotation. From previous experience and based on various references (particularly Dave Cheney’s Let’s Talk About Logging), the following levels should suffice for most Golang applications: Fatal, Error, Warn, Info and Debug. Let’s dig a bit deeper into these levels:

- Fatal:

- For logging errors/anomalies right when the application has entered a state in which a crucial business functionality is not working.

- With such errors, the application/service must be shutdown and operators/administrators notified immediately. The fix might not be straightforward.

- They should be accompanied by a stack-trace to simplify debugging.

FATALerrors are the unforeseen and infrequent ones - when this level occurs too frequently it means it’s being overused/misused [2.3].

- Error:

- For logging errors which are fatal but ‘scoped’ within a procedure [2.3]. Such errors require administrator/operator/developer intervention and the fix is relatively simple. For example, the wrong address was provided, or a server is not permitted to bind to a given port.

- Given that errors are ‘values’ in Go that can be returned from a function, one anti-pattern highlighted by Dave Cheney I’m guilty of in the past is logging an error then returning it to the caller. Then the parent caller logs it, then the grandparent caller logs it and so on such that the same error ends up being output multiple times. The logs become noisy and noisy logs tend to be less useful.

- The best course of action is simply to return the error and if necessary, add more context. For example, if I was unable to open a file, annotate the error with the file’s path then return it

- Warn:

- For logging expected anomalies which an application can recover from retrying, switching to a different node or to a backup and so on [2.1].

- Such anomalies are transient/temporary. For example, a HTTP request might fail but you expect that after a retry or two it should go through.

- Other anomalies have a pre-defined handling strategy: for example, if the primary database fails, the application is configured to switch to the backup (but we still want to record somewhere that the application could not access the primary)

- This then brings up an interesting discussion, once more brought up by Dave Cheney: if the application can eventually proceed normally, what’s even the point of logging warnings: either log them as ERROR or as INFO.

- Later on, we’ll have a brief section on logging as it pertains to telemetry and observability, for now, it’s worth pointing out that when using the RED Method majority of warn-level logs are better output as metrics so that operators can monitor the error-rates and set up the appropriate alerts

- Info:

- For logging normal application behavior to indicate that an expected happy-path event happened.

- There is a special class of logs termed ‘Audit logs’. These should not be logged as info-level logs and should have there own separate pathways and destination. In the next section I give a quick overview of audit logs.

- As an aside, for applications where configuration comes from multiple

sources (defaults, config files, command-line flags, environment variables

and so on) and other deploy-specific values such as the binary’s

version/commit-hash etc, a pattern that works for me is to log all these

values on start-up at

INFOlevel rather thanDEBUGlevel (it’s more likely that the logging level is set toINFOin prod). A huge class of operation errors stem from misconfiguration and this simplifies debugging/inspecting the config for operators (an alternative approach is to expose such information as metrics, but we’ll save this for the section on logging & telemetry :-D ) - It goes without saying, but it should be mentioned nonetheless, confidential information, secrets and keys should not be logged at all.

- Debug:

- For diagnostic information that should be helpful to developers

- Due to their verbosity, Debug logs should only be emitted during development and disabled in production

- Better yet, code that emits debug logs should not be checked into the main/deploy branch - it adds noise and you can always use a debugger or good old-fashioned print statements to trace steps in dev. The cost of adding logging (or more generally any instrumentation) isn’t just in the infrastructure to support routing, storage, queries etc, there’s also an implicit developer cost - with too many lines of code (LOC) dedicated just to logging, the underlying code handling the business logic risks being obscured. This increases both development and debugging time. That’s why we’ve got the B2I ratio (business-logic to instrumentation ratio) which can be computed with various tools and used to indicate if there’s too much LOC dedicated to logging

Audit Logs & Transactional Logs #

There are a special kind of logs that are categorized as Audit or Transactional logs.

They tend to deal with money, personally identifiable information (PII) or end-user actions. In ‘Logging in Action’, author Phil Wilkins further defines an audit event as ‘a record of an action, event, or data state that needs to be retained to provide a formal record that may be required at some future point to help resolve an issue of compliance (such as accounting processes or security).’

Additionally, from the Observability Whitepaper from CNCF we get the following definition:

Audit log - also called an audit trail, is essentially a record of events and changes. Typically, they capture events by recording who performed an activity, what activity was performed, and how the system responded. Often the system administrator will determine what is collected for the audit log based on business requirements.

Of key is the intended audience of such logs: unlike operational logs, they are not meant for developers/operators. Instead, they are meant for the “business” be it analysts or auditors or upstairs.

Therefore, it’s best to have separate pathways and destinations for such logs rather than shoe-horn them into operational logs. These logs may have separate confidentiality requirements, they may need to be retained much longer, maybe even for years and might even have to be deleted when requested by respective users as per privacy laws.

Usually, the business domain will dictate the audit/tx logs that need to be recorded.

Structured Logging #

The default approach to logging is ‘stringy’ or ‘string-based’ logging i.e. formatting attributes/parameters into the log messages to be output.

It works when a ‘human’ is directly going through the logs and all they need to query the logs is grep, awk and other unix-based CLI tools. It’s also suitable for CLI applications. However, if the logs have to be pre-processed before analyzing them using beefier tools, then structured logging should be used. In this Go discussion, github user jba describes structured logging in the following way:

Structured logging is the ability to output logs with machine-readable structure, typically key-value pairs, in addition to a human-readable message.

The format used for structured logs is usually JSON - its still human readable but is also machine-parse-able.

Protobuf can be used but it involves too much setup overhead with having to define messages upfront. Also, most logging aggregators are not protobuf friendly.

There are a couple of low-overhead/high-speed JSON parsing libraries such as yyjson (used by DuckDB) and simdjson (used by Clickhouse) so the overhead of parsing/querying JSON relative to binary formats should not be much of a concern. However, both JSON and stringy logs tend to take up a lot of space hence the need for lightweight, query-friendly compression schemes. Structured logs can also be wrangled into traditional database columns as a quick pre-processing step or they can be queried directly. I’ve written a separate post on how you can use DuckDB to derive structure from and query JSON.

For Go-based apps, there are a couple of structured logging libraries:

- Logrus. Being the oldest entry here, it’s credited for introducing structured loggging to Go. Relatively slow due to its API which necessitates the use of expensive methods and lots of allocations for serialization.

- Zap: High performance logging library from Uber. Highly configurable, suitable for large-scale projects

- Zerolog: An alternative to Zap that’s slightly faster while making fewer allocations. It’s also simpler to use with a more minimal API and few knobs to configure.

- slog: New kid on the block. Developed by the

Go-team - represents their attempt to standardize the interface for structured

logging in Go while providing a default alternative to the std library’s

logwhich is stringy.

For now, my preference is zerolog due to its minimal API (the speed/memory efficiency is a plus).

Logging, Observability & Telemetry #

When we add logging, we are making a system observable. “In control theory, observability is a measure of how well internal states of a system can be inferred from knowledge of its external outputs” [4.14]. These external outputs pertaining a system’s behavior are termed as Telemetry - “. Logging is one of the means of deriving telemetry. Others include tracing, collecting metrics, profiling, error reporting and collecting crash dumps.

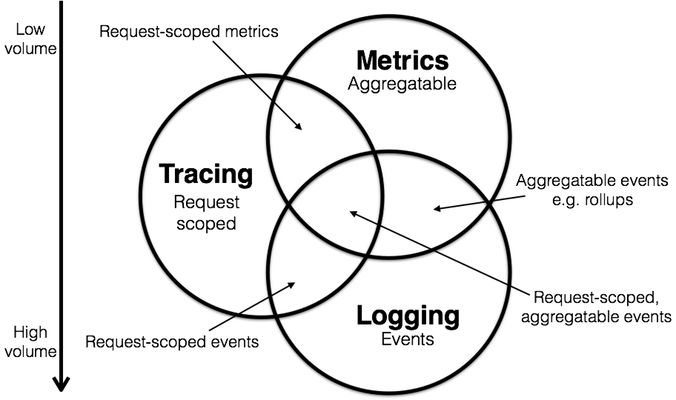

Logging, tracing and metrics form what’s often referred to as the “Three Observability Pillars”. Of importance for this post is how logging intersects with tracing and with metrics. Let’s start with metrics:

Logging & Metrics #

Metrics are defined as “a set of numbers that give information about a particular process or service”. These are sampled at configured time intervals and represent the state of the service over a given period.

Usually, for online services, metrics are used to monitor (The RED Method):

- Request Rates: number of requests per second

- Error rates: the number of requests that are failing per period

- Durations: the amount of time requests take

And for resources, (The USE Method):

- Utilization: how much time percentage was the resource busy for

- Saturation: amount of work resource has to do: often the queue length

- Errors: count of error events

With the frameworks above, it’s easy to see when/where to favor metrics over logging. This though isn’t just a matter of data representation or library usage: metrics are lightweight, metric collection is low-overhead and querying them is faster. Furthermore, metric systems such as Prometheus have extra features such as alerting systems and are easier to integrate into visualization tools.

Now, when to switch from metrics back to logs: A log entry is represented as a

text line, or better yet, a structured object. A metric output on the other hand

is represented as a name, timestamp and numerical value (usually a double).

Additionally, one can attach labels to a metric output: these are key-value

pairs that add context or uniquely identify a metric. So for example, if we’re

tracking the error rate at the endpoint /shop/checkout this can be represented

via a counter as:

checkout_errors{payment_method="paypal", region="EU"} 0.003129720687866211

This representation is Prometheus specific and the timestamp is added at the

destination. The labels for the metric are payment_method and region.Since

metrics are meant to be lightweight both in data size and for querying, adding

more and more labels defeats their purpose and is often the source of

significant slow-downs. As such, if a group of metrics really really needs to

have, let’s say 50 labels each, it’s best to switch back to (structured) logging

so as not to impact performance.

One last point wrt to metrics: I had earlier mentioned that basic configs and

build information can be output as INFO logs. Well, there’s an approach where

such information is also emitted as metrics, usually with the suffix _info.

For example, the Prometheus client for Python outputs the following:

# HELP python_info Python platform information

# TYPE python_info gauge

python_info{implementation="CPython",major="3",minor="8",patchlevel="10",version="3.8.10"} 1.0`

It might seem like an anti-pattern but this information is often useful to query on, for example, to see if the new version has introduced certain latencies compared to the previous version. Ultimately it’s all about convenience and surfacing the requisite information right where it’s needed.

Logging & Tracing #

Tracing involves capturing the entire lifecycle of a request i.e. the paths taken by the request plus any additional metadata as it’s handled across services.

A trace consists of a root span and one or more child spans. A span encompasses a single operation or unit of work and includes the trace ID, span ID, name, start and end timestamps, pointer to the parent (if non-root) and additional events and attributes. The root span represents the request from start to finish. All spans within a single trace have the same trace ID. A span’s context (trace & span ID, flags and state) can be propagated across nodes/services/processes. This allows for spans to be correlated and associated across a distributed system.

As far as tracing goes, all logs fall into one of these two categories:

- Request-scoped logs/Embedded logs: logs emitted as part of a request and can be attached to a span

- Standalone Logs: non-request logs i.e. logs not embedded inside of a span and are recorded elsewhere

The question then is how to handle request-scoped logs: we want these logs and traces to complement each other plus avoid duplication while also be able to use the desired tools and libraries.

As mentioned prior, spans can contain events and attributes. Therefore, request-scoped logs can be attached to traces as span events. And if structured logging is being used, the attributes that would normally be part of the log entry can instead be captured as Span attributes.

However, in my opinion, logs should be emitted separately from traces. Trace APIs for Golang such as OpenTelemetry haven’t yet stabilized support for logging. Also trace destinations such as Jaeger don’t quite yet provide rich extensive querying for logs.

Rather than insert logs into traces, trace IDs and span IDs should be added as attributes to logs. This allows for logs to be aggregated and queried separately and when correlating logs to traces (and vice versa), the trace & span IDs are used for lookups.

For example, when using zerolog for logging, span context can be added to logs as follows:

First define the hook:

func traceHook(ctx context.Context) zerolog.HookFunc {

return func(

e *zerolog.Event,

level zerolog.Level,

message string,

) {

// Enabled: returns false if event is going to be filtered out by

// log level or sampling

if level == zerolog.NoLevel || !e.Enabled() || ctx == nil {

return

}

span := trace.SpanFromContext(ctx)

if !span.IsRecording() {

e.Bool("trace", false)

return

}

// Add traceIDs and spanIDs to logs

sc := span.SpanContext()

if sc.HasTraceID() {

e.Str("traceId", sc.TraceID().String())

}

if sc.HasSpanID() {

e.Str("spanId", sc.SpanID().String())

}

}

}

Then define a function for creating loggers:

var initLoggerOnce sync.Once

var zeroLogger zerolog.Logger

func GetLogger(ctx context.Context, app string) zerolog.Logger {

initLoggerOnce.Do(func() {

l := zerolog.New(os.Stdout).

Level(zerolog.TraceLevel).

With().

Caller().

Timestamp().

Str("app", app).

Logger()

zeroLogger = l

})

return zeroLogger.Hook(traceHook(ctx))

}

GetLogger can be invoked at the beginning of a request operation and used

throughout. Each log entry will have a traceID and spanID attribute.

Let’s finish off with the following Venn diagram, credits to Peter Bourgon in Metrics, tracing, and logging:

It’s important to know where logging, tracing and metrics intersect and where they don’t. Client side libraries and frameworks are evolving fast to provide a single API for all three. Observability platforms too are emerging and evolving to accommodate these signals within a single package/service. The goal as always remains being able to understand and troubleshoot running systems.

References #

General References

Logging Levels:

Let’s talk about logging - Dave Cheney: link

Understanding Logging Levels - What They Are & How To Use Them - Rafal KuĆ

Structured Logging

- Structured Logging - James Turnbull

- structured, leveled logging - jba - github discussion

- Proposal: standard Logger interface - Peter Bourgon, Chris Hines

- A Complete Guide to Logging in Go with Zerolog - Ayooluwa Isaiah - BetterStack

- A Comprehensive Guide to Logging in Go with Slog - Ayooluwa Isaiah - BetterStack

Logging, Telemetry & Observability

- Distributed Tracing — we’ve been doing it wrong - Cindy Sridharan

- ‘Metrics, tracing and logging’ - Peter Bourgon

- ‘Logging v. instrumentation’ - Peter Bourgon

- ‘Logs and Metrics’ - Cindy Sridharan

- ‘Logs vs Structured Events’ - Charity Majors

- ‘Lies My Parents Told Me (About Logs)’ - Charity Majors

- ‘The RED Method: How To Instrument Your Services’ - Tom Wilkie

- Cloud Observability In Action - Michael Hausenblas

- Prometheus: Up & Running - Julien Pivotto, Brian Brazil

- A simple way to get more value from tracing - Dan Luu

- Why Tracing Might Replace (Almost) All Logging

- Dapper, A Large Scale Distributed Systems Tracing Infrastructure - Paper Review - Adrian Colyer

- Logs Data Model - OpenTelemetry

- Observability Whitepaper - CNCF